Secret Service fumbled response after gunman hit White House residence in 2011

The inwards track on Washington politics.

*Invalid email address

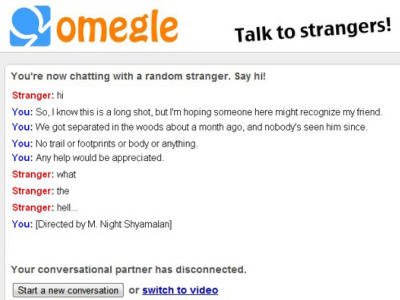

Law enforcement officers photograph a window at the White House in this Nov. 16, 2011, file photo. A bullet shot at the house hit an exterior window of the White House and was stopped by ballistic glass, the Secret Service said at the time. (Haraz N. Ghanbari/AP)

The gunman parked his black Honda directly south of the White House, in the dark of a November night, in a closed lane of Constitution Avenue. He pointed his semiautomatic rifle out of the passenger window, aimed directly at the home of the president of the United States, and pulled the trigger.

A bullet smashed a window on the 2nd floor, just steps from the very first family’s formal living room. Another lodged in a window framework, and more pinged off the roof, sending bits of wood and concrete to the ground. At least seven bullets struck the upstairs residence of the White House, flying some seven hundred yards across the South Lawn.

President Obama and his wifey were out of town on that evening of Nov. 11, 2011, but their junior daughter, Sasha, and Michelle Obama’s mother, Marian Robinson, were inwards, while older daughter Malia was expected back any moment from an outing with friends.

Secret Service officers primarily rushed to react. One, stationed directly under the second-floor terrace where the bullets struck, drew her .357 handgun and ready to crack open an emergency gun box. Snipers on the roof, standing just twenty feet from where one bullet struck, scanned the South Lawn through their rifle scopes for signs of an attack. With little camera surveillance on the White House perimeter, it was up to the Secret Service officers on duty to figure out what was going on.

Then came an order that astonished some of the officers. “No shots have been fired. . . . Stand down,” a supervisor called over his radio. He said the noise was the backfire from a nearby construction vehicle.

That guideline was the very first of a string of security lapses, never previously reported, as the Secret Service failed to identify and decently investigate a serious attack on the White House. While the shooting and eventual arrest of the gunman, Oscar R. Ortega-Hernandez, received attention at the time, neither the bungled internal response nor the potential danger to the Obama daughters has been publicly known. This is the very first total account of the Secret Service’s confusion and the missed clues in the incident — and the anger the president and very first lady voiced as a result.

By the end of that Friday night, the agency had confirmed a shooting had occurred but wrongly insisted the gunfire was never aimed at the White House. Instead, Secret Service supervisors theorized, gang members in separate cars got in a gunfight near the White House’s front lawn — an unlikely script in a relatively quiet, touristy part of the nation’s capital.

It took the Secret Service four days to realize that shots had hit the White House residence, a discovery that came about only because a housekeeper noticed violated glass and a chunk of cement on the floor.

This report is based on interviews with agents, investigators and other government officials with skill about the shooting. The Washington Post also reviewed hundreds of pages of documents, including transcripts of interviews with officers on duty that night, and listened to audio recordings of in-the-moment law enforcement radio transmissions.

Secret Service spokesman Ed Donovan declined to comment. A spokesman for the White House also declined to comment.

The scene exposed problems at numerous levels of the Secret Service, and it demonstrates that an organization long seen by Americans as an elite force of selfless and very skilled patriots — willing to take a bullet for the good of the country — is not always up to its job.

Just this month, a man carrying a knife was able to leap the White House fence and sprint into the front door. The agency was also embarrassed by a two thousand twelve prostitution scandal in Cartagena, Colombia, that exposed what some called a wheels-up, rings-off culture in which some agents treated presidential trips as an chance to party.

The deeds of the Secret Service in the minutes, hours and days that followed the two thousand eleven shooting were particularly problematic. Officers who were on the scene who thought gunfire had most likely hit the house that night were largely disregarded, and some were afraid to dispute their bosses’ conclusions. Nobody conducted more than a cursory inspection of the White House for evidence or harm. Key witnesses were not interviewed until after bullets were found.

Moreover, the suspect was able to park his car on a public street, take several shots and then speed off without being detected. It was sheer luck that the shooter was identified, the result of Ortega, a troubled and jobless 21-year-old, wrecking his car seven blocks away and leaving his gun inwards.

The response infuriated the president and the very first lady, according to people with direct skill of their reaction. Michelle Obama has spoken publicly about fearing for her family’s safety since her hubby became the nation’s very first black president.

Her concerns are well founded — President Obama has faced three times as many threats as his predecessors, according to people briefed on the Secret Service’s threat assessment.

“It was obviously very scaring that someone who didn’t indeed plan it that well was able to shoot and hit the White House and people here did not know it until several days later,” said William Daley, who was White House chief of staff at the time.

Daley said he recalls the late discovery of the bullets jiggling up the Obamas and their staffs. The Secret Service could not have prevented the shooting, Daley said, but it should have determined more quickly what happened.

“The treating of this was not good,” he said.

By the time Ortega shot at the White House, President Obama and the very first lady were in San Diego on their way to Hawaii for the Veterans Day weekend.

With the very first duo gone, the Secret Service staff at the White House slipped into what some termed a “casual Friday” mode.

By 8:30 p.m., most of the Secret Service agents and officers on duty were coming to the tail end of a quiet shift.

An undercover agent in charge of monitoring the White House perimeter for suspicious activity, McClellan Plihcik, had left with a more junior officer to pack up his service car at a gas station about a mile away.

On the White House’s southern border, a few construction workers were milling about. D.C. Water trucks, arriving on Constitution Avenue to clean sewer lines, had just parked in the lane closed off by crimson cones on the White House side of the street.

It was near that spot that Ortega pulled over his black one thousand nine hundred ninety eight Honda Accord.

Ortega had left his Idaho home about three weeks earlier, during a time his friends said he had been acting increasingly paranoid. He kept launching into tirades about the U.S. government attempting to control its citizens, telling President Obama “had to be stopped.”

He had arrived in Washington on Nov. 9. He had one hundred eighty rounds of ammunition and a Romanian-made Cugir semiautomatic rifle, similar to an AK-47, that he had purchased at an Idaho gun shop.

Now, in striking distance of the president’s home, Ortega raised his weapon.

A woman in a taxi stopped at a nearby stoplight instantaneously took to Twitter to describe the deeds of “this crazy stud.”

“Driver in front of my cab, STOPPED and fired five gun shots at the White House,” she wrote, adding, “It took the police a while to react.”

Another witness — a visiting neuroscientist who was railing by in an airport shuttle van — later told investigators he had seen a man shooting out of a car toward the White House.

On the rooftop of the White House, Officers Todd Amman and Jeff Lourinia heard six to eight shots in quick succession, likely semiautomatic fire, they thought. They scurried out of their shedlike booth, readied their rifles and scanned the southern fence line.

Under the Truman Balcony, the second-floor terrace off the residence that overlooks the Washington Monument, Secret Service Officer Carrie Johnson heard shots and what she thought was debris falling overhead. She drew her handgun and took cover, then heard a radio call reporting “possible shots fired” near the south grounds.

Johnson called the Secret Service’s joint operations center, at the agency’s headquarters on H Street Northwest, to report she was cracking into the gun box near her post, pulling out a shotgun. She substituted the buckshot inwards with a more powerful slug in case she needed to engage an attacker.

The shots were fired about fifteen yards away from Officers William Johnson and Milton Olivo, who were sitting in a Chevrolet Suburban on the Ellipse near Constitution Avenue.

They could smell acrid gunpowder as they leaped out of their vehicle, hearts pounding. Johnson took cover behind some flowerpots. Olivo grabbed a shotgun from the Suburban’s back seat and crouched by the vehicle.

William Johnson noticed a nosey clue as he crouched in the crisp autumn air — leaves had been gargled away in a line-like pattern, perhaps by air from a firearm muzzle. It created a path of exposed grass pointing from Constitution Avenue north toward the White House.

Then another call came over the radio from a supervising sergeant — the one ordering agents to stand down.

The call led to some confusion and surprise, especially for officers who felt sure they had heard shots. Nevertheless, many complied, holstering their guns and turning back to their posts.

But William Johnson knew shots were fired and got on his radio to say so. “Flagship,” he said, using the code name for the instruction center, “shots fired.”

Ortega, meantime, was driving away “like a maniac,” the woman in the cab wrote on Twitter.

He was speeding down Constitution Avenue toward the Potomac Sea at about sixty mph, according to witnesses.

Ortega narrowly missed striking a duo crossing the street before he swerved and crashed his car.

Three women walking nearby heard the crash, and one called nine hundred eleven on a cellphone. As they walked closer to the scene, the women eyed the Honda spun around, headlights glaring at oncoming traffic, half on the on-ramp to the Roosevelt Bridge carrying Interstate sixty six into Virginia. The driver’s-side door was flung open. The radio was blaring. The driver was gone.

At the same time, Park Police and Secret Service patrol cars were beginning to swarm the bridge area. Nestled in the driver console was a semiautomatic onslaught rifle, with nine shell casings on the floor and seat.

Plihcik, the special agent who had been gassing up his patrol car, was among those arriving on the scene. A homeless man told him he had seen a youthfull white masculine running from the vehicle after the crash and heading toward the Georgetown area.

Amid conflicting radio chatter, including a Secret Service dispatcher calling into nine hundred eleven with contradictory descriptions of vehicles and suspects, police began looking for the wrong people: two black studs supposedly fleeing down Rock Creek Parkway.

The man who had shot at the White House had disappeared on foot into the Washington night, with the Secret Service still attempting to lump together what he had done.

Back in the White House, key people in charge of the safety of the president’s family were not originally aware that a shooting had occurred.

Because officers guarding the White House grounds communicate on a different radio frequency from the one used by agents who protect the very first family, the agent assigned to Sasha learned of the shooting a few minutes later from an officer posted nearby.

The White House usher on duty, whose job is tending to the very first family’s needs, got delayed word as well. She instantaneously began to worry about Malia, who was supposed to be arriving any minute. The usher told the staff to keep Sasha and her grandmother inwards. Malia arrived with her detail at 9:40 p.m., and all doors were locked for the night.

The Secret Service’s witness commander on duty, Capt. David Simmons, had been listening to the confusing radio chatter since the very first reports of possible shots.

When word came of the wrecked Honda, Simmons left the instruction center and drove to the scene at the foot of the Roosevelt Bridge.

It was up to Simmons to determine whether the events of that night appeared to be an attack on the White House. After consulting with investigators and calling his bosses at home to confer, he turned the case over to the U.S. Park Police, the agency with jurisdiction over the grounds near the White House.

In effect, the Secret Service had concluded there was no evidence linking the shooting to the White House.

U.S. Park Police spokesman David Schlosser told reporters at the time that the connection was a big coincidence. “The thing that makes it of interest is simply the location, you know, a bit like real estate,” he said.

At the time of the shooting, President Obama had been sitting courtside on the USS Carl Vinson warship in the California’s Coronado Bay, watching the University of North Carolina and Michigan State University basketball teams play on the flight deck. He was getting ready to be interviewed by ESPN at nine p.m.

Forty-five minutes later, the president and Michelle Obama climbed aboard Air Force One, strapped for a trade summit in Honolulu, unaware that a man had taken several shots at their living quarters.

The next day, things seemed to have lodged down at the White House.

Officer Carrie Johnson, who had heard debris fall from the Truman Balcony the night before, listened during the roll call before her shift Saturday afternoon as supervisors explained that the gunshots were from people in two cars shooting at each other.

Johnson had told several senior officers Friday night that she thought the house had been hit. But on Saturday she did not challenge her superiors, “for fear of being criticized,” she later told investigators.

Tho’ the Park Police was now in charge of the investigation, Secret Service agents continued to assist, using social media and other sources to locate witnesses, such as the tweeting taxi passenger, and people who knew Ortega.

Investigators did not issue a national lookout to notify law enforcement that Ortega was wished. If they had, Ortega could have been arrested that Saturday in Arlington County, Va., where police responded to a call about a man behaving oddly in a local park. They questioned Ortega but had no idea he was a suspect in a shooting, and they let him go.

The Park Police did not obtain a warrant for Ortega on weapons charges until that Sunday. A Park Police spokeswoman, reached this Friday, declined to comment, telling the agency needed more time to review the scene.

Meantime, Secret Service agents, who had been learning from Ortega’s friends and family that he was obsessed with President Obama, began canvassing the D.C. area to locate him.

The situation at the White House remained quiet until Tuesday morning. President Obama was continuing from Hawaii to Australia. But the very first lady had returned to Washington on an overnight flight. She had gone upstairs to take a nap shortly after arriving home early that morning.

Flying back on her plane was Secret Service Director Mark Sullivan. At that time, his agents were learning that Ortega, still at large, appeared to be obsessed with the president. The scene had not yet risen to the level of a confirmed threat that the Secret Service would share with the very first duo, according to people familiar with agency practice.

Reginald Dickson, an assistant White House usher, had come to work early to prepare the house for the very first lady.

Around noon, a housekeeper asked Dickson to come to the Truman Balcony, where she showcased him the cracked window and a chunk of white concrete on the floor.

Dickson eyed the bullet slot and cracks in the antique glass of a center window, with the intact bulletproof glass on the inwards. Dickson spotted a dent in another window sill that turned out to be a bullet lodged in the wood.

Dickson called the Secret Service agent in charge of the elaborate.

All of a sudden, Ortega was no longer just a man who had abandoned a car with a rifle inwards. He was now a suspect in an assassination attempt on the president of the United States — and he was about to become the target of a national manhunt.

Daley, the White House chief of staff, was alerted by aides about the discovery on the 2nd floor of the residence.

The very first lady was still napping, and Daley and his aides knew it was their job to tell her. They debated whether they should wake her up and give her the news.

They determined, according to people familiar with the discussions, to let her sleep. Instead, they concluded, they would brief the president and let him tell his wifey.

But someone else told her very first.

Dickson, the usher, went upstairs to the third floor to see how Michelle Obama was doing.

He assumed she knew about the bullets and began describing the discovery.

But she was aghast — and then quickly furious. She wondered why Sullivan had not mentioned anything about it during their long flight back together from Hawaii, according to people familiar with the very first lady’s reaction.

That afternoon, Secret Service investigators for the very first time began interviewing officers and agents who had been on the grounds the previous Friday night.

Authorities put out an all-points bulletin for Ortega and circulated his picture. Local police officers up and down the Eastern Seaboard were tasked with checking train and bus stations.

A team of FBI agents met early that evening to plan for taking over the investigation and securing the crime scene at the White House.

At 7:45 a.m. the next day, FBI agents arrived at the White House elaborate.

They interviewed some of the Secret Service officers who were on duty that Friday night and scoured the Truman Balcony and nearby grounds for casings, bullet fragments and other evidence.

The agents that day found $97,000 worth of harm.

At that same time, state troopers were headed to a Hampton Inn in Indiana, Pa. A desk clerk, on alert after Secret Service agents found out Ortega had stayed there and circulated his picture, called police after recognizing the man with a distinctive tattoo on his neck. They arrested Ortega and kept him chained at his feet and arms in a holding cell until FBI agents could arrive to question him.

Back at the White House, Michelle Obama was worried about how the scene of agents on the family balcony might upset her daughters. She relayed a special request that the FBI team finish their work on the balcony by Two:35 p.m., before Sasha and Malia came home from school.

The very first lady was still upset when her spouse arrived home five days later from Australia. The president was fuming, too, former aides said. Not only had their aides failed to instantaneously alert the very first lady, but the Secret Service had stumbled in its response.

“When the president came back . . . then the s— indeed hit the fan,” said one former aide.

Tensions were high when Sullivan was called to the White House for a meeting about the incident. Michelle Obama addressed him in such a acute and raised voice that she could be heard through a closed door, according to people familiar with the exchange. Among her many questions: How did they miss bullets from an onslaught rifle lodged in the walls of her home?

Sullivan disputed this account of the meeting but declined to characterize the encounter, telling he does not discuss conversations with the very first lady.

Ortega was eventually charged with attempted assassination. His attorneys insisted he had no idea what he was doing. He pleaded guilty to slightly lesser charges and was sentenced to twenty five years in prison.

The next year, the Colombia prostitution scandal rocked the agency’s reputation. Sullivan retired from the agency in two thousand thirteen to commence a private security rigid. President Obama named the very first woman to head the service, Julia Pierson, with hopes she could help end Cartagena-like embarrassments.

Yet, on Capitol Hill and among many former Secret Service officials, the two thousand eleven shooting was a sign of far deeper troubles. For them, no duty is more sacred than protecting the life of the president and his family, and on this night a man almost got away with shooting into his house. In this case, they fear, a more powerful weapon might have pierced the residence, or the Obama daughters could have been on the balcony.

“This is symptomatic of an organization that is not moving in the right direction,” Rep. Jason Chaffetz (Utah), a leading Republican on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, said in an interview. The committee, which oversees the Secret Service, has invited the director to testify at a Tuesday hearing on security issues.

A subsequent internal security review found that the incident illustrated serious gaps.

The Secret Service, for example, could not use any of the dozens of ShotSpotter sensors installed across the city to help police pinpoint and trace gunshots. The closest sensor was more than a mile away, too far to track Ortega’s shots.

Sullivan acknowledged in closed congressional briefings that the agency lacked basic camera surveillance that could have helped agents see the attack and swarm the gunman instantaneously.

Some of the technology issues have since been addressed, according to officials. The agency added a series of surveillance cameras in 2012, providing authorities a utter view of the perimeter.

Alice Crites and Julie Tate contributed to this report.